Table of Contents

When I first encountered images of the Visconti-Sforza tarot cards, I found myself staring at them for much longer than I’d expected. There’s something almost hypnotic about these hand-painted treasures from the mid-15th century. Perhaps it’s the way gold leaf catches light differently in each photograph, or maybe it’s knowing that actual Renaissance nobles once held these very cards. Whatever draws us to them, the Visconti-Sforza deck offers a fascinating window into both the origins of tarot and the cultural world of Renaissance Milan.

Created sometime between 1428 and 1447 for Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan, and later associated with Francesco Sforza who married into the family, this deck represents one of our most complete glimpses into early tarot history. But calling it simply “tarot” might be misleading. These cards were created for a game called “triumph” or “trionfi,” which bears some resemblance to modern tarot but served primarily as entertainment for the noble court.

The Artistic Marvel of Hand-Painted Cards

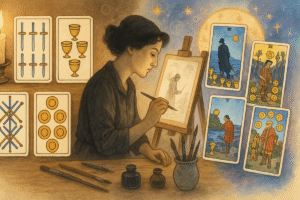

The sheer craftsmanship of these cards still amazes me. Each one was individually painted on card stock, with intricate details that would make modern collectors weep with envy. The artists, likely from the workshop of Bonifacio Bembo, used tempera paint and gold leaf to create images that feel both otherworldly and surprisingly intimate.

When you look at the Empress card, for instance, you might notice how her dress seems to shimmer with an almost ethereal quality. The gold threading appears to catch light even in museum photographs. I sometimes wonder what it must have felt like to hold such a card, feeling its slight thickness between your fingers, seeing how the metallic accents shifted as you tilted it toward candlelight.

The artistic style reflects the International Gothic movement that was flourishing in northern Italy during this period. You can see this in the flowing lines of the figures’ clothing, the delicate facial expressions, and the way space is organized within each card’s frame. These weren’t mass-produced playing cards; they were miniature works of art, each one a testament to the skill and patience of Renaissance craftsmen.

A Window into Renaissance Society

What strikes me most about studying these cards is how much they reveal about the world that created them. The court cards, in particular, offer glimpses into the social hierarchies and cultural values of 15th-century Milan. The clothing styles, the architectural details visible in backgrounds, even the way figures hold themselves all speak to specific historical moments.

The Knight of Swords, for example, displays armor and weaponry that would have been cutting-edge military technology for its time. When I examine the details of his horse’s tack or the specific style of his helmet, I’m looking at a catalog of what wealthy nobles considered important enough to preserve in art. These weren’t generic medieval fantasy images; they were contemporary portraits of power and status.

The religious imagery throughout the deck also tells us something significant about the spiritual landscape of the era. The major arcana cards we recognize today, like the Pope and the Angel (which we now call Judgement), reflect a world where religious authority was central to daily life and political power. Yet there’s something in these images that feels more personal somehow, less dogmatic than you might expect from formal religious art of the period.

The Original Game and Its Social Context

Here’s where things get particularly interesting, at least for me. These cards weren’t created for the kind of contemplative, reflective practice that many of us associate with tarot today. They were designed for a trick-taking card game that was probably similar to modern bridge or spades, but with an additional layer of special trump cards.

The game of trionfi was apparently quite popular among Italian nobility. Players would try to take tricks using the numbered suit cards (swords, cups, coins, and batons), but the triumph cards could trump any regular suit. The exact rules have been lost to history, which leaves us to imagine how these gorgeous cards moved through players’ hands during long evenings at the Sforza court.

I find myself curious about the social dynamics of these games. Who was allowed to play? How did the symbolism of the cards influence the way people thought about the game itself? When someone played The World card to win a trick, did it feel symbolically significant, or was it simply good strategy?

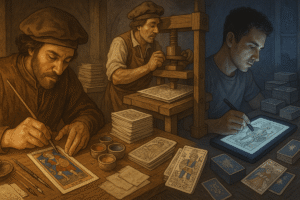

The transition from this gaming context to the more mystical associations we have with tarot today happened gradually over several centuries. By the 18th century, writers and occultists had begun to attach divinatory meanings to tarot cards, but that came much later. The Visconti-Sforza cards remind us that tarot’s origins lie in entertainment and art, not prophecy.

Mysteries and Missing Pieces

Not everything about the Visconti-Sforza deck is clear, which perhaps makes it even more intriguing. Several cards from the original set are missing, and historians aren’t entirely certain about the deck’s complete composition. Some cards that exist in other early decks don’t appear in the surviving Visconti-Sforza collection, while some cards that do exist seem unique to this particular set.

The Devil card, for instance, is missing entirely from the surviving collection. Whether it was never created, was lost, or was deliberately removed at some point remains unknown. This absence creates an interesting gap in our understanding of how the major arcana sequence developed. What might this missing card have looked like? How would 15th-century Milanese artists have depicted such a figure?

There’s also the question of variant cards. Some versions of the deck include cards that don’t appear in standard modern tarot, such as Faith, Hope, and Charity replacing some of the more familiar major arcana. These variations suggest that the “standard” tarot structure we know today was still evolving during this period.

Reflections on Artistic Legacy

When I think about the Visconti-Sforza deck’s influence on later tarot designs, I’m struck by both continuity and change. Many of the visual elements we associate with certain cards can be traced back to these Renaissance originals. The Hanged Man’s distinctive pose, the architectural details in The Tower, the flowing robes of The Hermit, these visual motifs have echoed through centuries of tarot design.

Yet there’s also something irreplaceable about the original artistic vision. Modern tarot decks, no matter how beautiful, can’t quite replicate the sense of historical weight these cards carry. They were created in a world so different from ours that they feel almost alien, yet the human figures depicted in them express emotions and attitudes that feel surprisingly familiar.

I sometimes wonder what questions we might ask ourselves when contemplating these historical images. How do the faces in these cards reflect our own inner states? What aspects of power, creativity, or spiritual seeking do we recognize in these Renaissance nobles and allegorical figures? The cards invite us to consider how human experiences of growth, challenge, and transformation have remained consistent across centuries, even as the external trappings of life have changed dramatically.

Personal Encounters with History

There’s something deeply moving about seeing reproductions of these cards, knowing that they survived wars, political upheavals, and the simple passage of time. The fact that we can still examine the brushstrokes of artists whose names we barely know feels almost miraculous.

If you ever have the opportunity to see high-quality reproductions of the Visconti-Sforza cards, I’d encourage you to spend time with them slowly. Notice the small details: the expressions on faces, the patterns in clothing, the way light seems to play across golden surfaces. These aren’t just historical artifacts; they’re invitations to connect with the artistic vision and cultural world of Renaissance Milan.

Perhaps most remarkably, these cards continue to inspire contemporary artists and tarot enthusiasts. The visual vocabulary they established still influences deck design today, more than 500 years after their creation. In that sense, the Visconti-Sforza cards represent not just the beginning of tarot’s visual tradition, but an ongoing conversation between past and present about how we understand symbolism, art, and the human experience.

The Visconti-Sforza deck reminds us that what we now call tarot began as something quite different from its current form. Yet in their beauty, craftsmanship, and enduring visual power, these cards continue to speak to something timeless in human nature. They invite us to reflect on our own relationship with art, history, and the symbols that help us make sense of our inner and outer worlds.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where can I see the original Visconti-Sforza cards in person?

The surviving cards are split across three locations: 35 cards are housed at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City, 26 cards can be found at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, Italy, and 13 cards remain in the private Colleoni family collection, also in Bergamo. The Morgan Library occasionally displays their cards and offers special viewing opportunities, making it the most accessible location for those wanting to see these historical treasures firsthand.

Which cards are missing from the original deck?

Four cards from the most complete Visconti-Sforza set have been lost to history: The Devil, The Tower, the Three of Swords, and the Knight of Coins. Modern reproductions typically include recreated versions of these missing cards, though the artistic interpretations vary significantly between different publishers and no one knows exactly what the originals looked like or whether The Devil and The Tower were even created in the first place.

Can I buy a reproduction of the Visconti-Sforza deck?

Yes, several publishers produce reproduction decks, with U.S. Games Systems and Lo Scarabeo being among the most well-known. These reproductions vary in quality, size, and how they handle the missing cards, with some featuring restored versions that look pristine and others showing the cards in their current weathered state complete with chipped paint and the pin holes that appear at the top of each original card.

Why do the cards have holes punched in them?

The pin holes at the top center of most cards suggest they may have been strung together for storage or possibly lent out as artist’s models for other painters to copy. This practice of using the cards as artistic references might explain why several other incomplete 15th-century decks contain cards clearly copied from the Visconti-Sforza originals, sometimes in reverse or with slight variations.