Table of Contents

There’s something quietly magical about watching a character come to life on the page. You know the moment I’m talking about. When they stop being a collection of traits and suddenly become someone real, someone who surprises you with their choices. I’ve found that tarot offers a unique pathway into that kind of character depth, not through prediction or mysticism, but through reflection and creative questioning.

The practice of using tarot for character development has grown steadily among writers over the past few years. Perhaps it makes sense. Fiction writing and tarot reading both involve pattern recognition, symbolic thinking, and the ability to sit with ambiguity. Both ask us to look beneath surfaces. When you draw a card for your protagonist, you’re not consulting an oracle. You’re creating a mirror that reflects back questions you might not have thought to ask.

Understanding Tarot as a Creative Tool

Before we explore the spread itself, it helps to reframe what tarot actually does in a creative context. Think of each card as a visual prompt, dense with symbolism that your mind naturally wants to decode. The Hermit doesn’t tell you your character is lonely. Instead, it might prompt you to ask: Where does this person go when they need solitude? What wisdom have they gathered in isolation? What light are they carrying into dark places?

This reflective approach transforms tarot from fortune telling into something more like a structured brainstorming session. The cards offer starting points, not destinations. They give you permission to explore contradictions in your character’s psychology. A single card contains multitudes, which means your interpretation will always be filtered through your unique creative lens and your specific character’s circumstances.

I think what draws writers to this method is the element of productive surprise. When you deliberately randomize your creative prompts, you break out of habitual thinking patterns. You might have unconsciously decided your protagonist is brave, but then you draw the Five of Cups. Suddenly you’re considering: What loss haunts them? How does grief shape their decisions? The card doesn’t answer these questions. It simply insists you ask them.

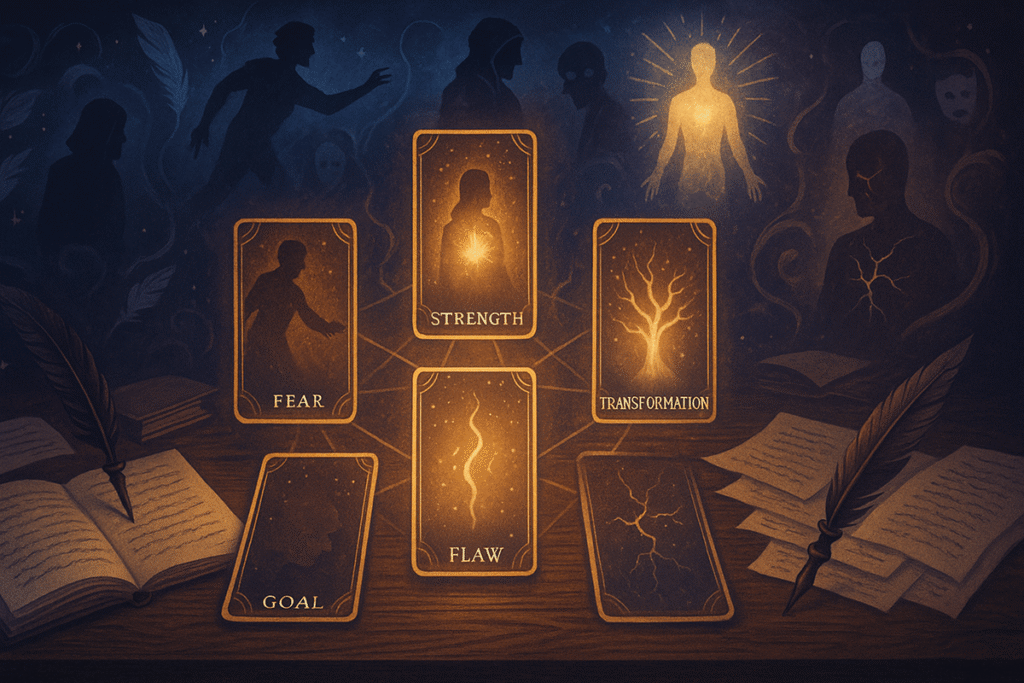

The Five Position Character Architecture Spread

This spread works best when you approach it with a specific character already forming in your mind. Not fully realized, perhaps, but present enough that you can begin asking them questions. You’ll draw five cards, each occupying a distinct position that maps onto a different layer of psychological complexity.

Layout the cards in a cross pattern if you prefer visual arrangements, or simply in a line. The physical positioning matters less than the mental space you create around each draw. Take your time between cards. Let each one settle before moving to the next.

Position One: The Conscious Goal

This first position explores what your character thinks they want. Their stated objective. The thing they would tell a stranger at a party if asked about their ambitions. Draw your card and sit with it for a moment.

If you draw something like the Three of Pentacles, you might explore: Does your character seek recognition for their craftsmanship? Are they building something tangible? How do they define success in collaborative spaces? Notice I’m phrasing these as questions, not answers. The card shows you a direction to walk, not a destination that’s fixed.

Your character’s conscious goal might be completely reasonable or wildly misguided. They might pursue it with clarity or confusion. The Ten of Cups could suggest someone seeking domestic harmony, while the Seven of Swords might indicate a character consciously chasing freedom through morally ambiguous means. Both are valid. Both are interesting.

Consider writing a short paragraph from your character’s point of view about this goal. Let them explain it in their own words, even if you suspect they’re lying to themselves. Especially if they’re lying to themselves, actually.

Position Two: The Subconscious Fear

Here’s where things get more complex. This position isn’t about what your character knows they fear. It’s about the terror that operates below their awareness, the thing that shapes their choices without their permission.

When you draw this card, you’re looking for the shadow material. The Eight of Swords might suggest someone unconsciously terrified of their own agency, someone who has internalized the belief that they’re trapped. They might not know they’re doing this. They might actively argue against it if confronted. But their actions reveal the pattern.

The Devil could indicate a fear of losing control, manifesting as controlling behavior they rationalize in other ways. The Tower might show someone unconsciously afraid that stability itself is an illusion, leading them to sabotage secure situations before they can collapse naturally.

This is often the most generative position in the spread. Subconscious fears create incredible dramatic irony. Your readers can see the pattern before your character does. That gap between awareness and behavior generates tension that feels earned rather than manufactured.

Think about how this fear might have originated. You don’t need to write a detailed backstory immediately, but having a sense of when this pattern started helps you understand how deeply rooted it is. Some fears are situational. Others are architectural, load bearing walls in your character’s psychology that can’t be removed without careful reconstruction.

Position Three: The Greatest Strength

Every interesting character has genuine capability in some area. This position helps you identify what your character does well, what resource they can actually draw upon when circumstances demand it.

The Strength card here would be almost too on the nose, but it could suggest someone whose power lies in gentle persistence rather than force. The Queen of Swords might indicate intellectual clarity and the ability to cut through emotional confusion. The Star could point to hope as a practical skill, the capacity to envision better futures even in dark circumstances.

I find it useful to think about whether this strength is recognized or hidden. Does your character know they possess this quality? Do they value it, or do they take it for granted? Sometimes our greatest capabilities are the ones we dismiss because they come easily to us.

Also consider whether this strength connects to their conscious goal or contradicts it. A character with the Knight of Pentacles’ steady reliability who consciously seeks adventure creates interesting internal friction. They have the tools to succeed at something other than what they think they want.

Position Four: The Fatal Flaw

Not fatal in the sense that it kills them, necessarily, though it might. Fatal in the sense that it’s the crack in their foundation, the weakness that makes them human and vulnerable and real. Without this, you don’t have a character. You have a superhero, and even superheroes need flaws to be compelling.

The Five of Pentacles might suggest someone whose flaw is refusing help, insisting on struggling alone even when support is available. The Two of Swords could indicate decision paralysis, an inability to commit that keeps them perpetually suspended between options. The King of Wands reversed might show someone whose confidence has curdled into arrogance.

Think about how this flaw intersects with their subconscious fear. Often, our flaws are defensive mechanisms that once protected us but now limit us. A character who fears vulnerability might develop the flaw of emotional unavailability. Someone afraid of insignificance might become insufferably attention seeking.

The most interesting flaws are the ones that make sense from inside the character’s perspective. They’re not random weaknesses but logical extensions of their psychology and history. Your readers should be able to understand why this person developed this particular limitation, even if they wish the character would overcome it.

Position Five: The Ultimate Transformation

This final position explores potential rather than certainty. Where might this character’s journey lead them? What psychological shift becomes possible if they engage with their fears, leverage their strengths, and reckon with their flaws?

Drawing Judgment here might suggest a character capable of radical self evaluation and rebirth. The Six of Swords could indicate someone learning to leave behind what no longer serves them. The Ace of Wands might point toward creative reinvention and new beginnings.

Notice I keep using words like “might” and “could.” That’s deliberate. This position shows you possibilities, not inevitabilities. Your character might achieve this transformation fully, partially, or not at all. Tragedy is always an option. Some characters are too broken or too stubborn to change, and that’s legitimate too.

Consider whether this transformation resolves their internal contradictions or simply reorganizes them into a more sustainable configuration. Not every character arc ends in total healing. Sometimes growth means learning to live with your damage more skillfully.

Integrating the Reading Into Your Writing Process

Once you’ve drawn all five cards and spent time with each position, you’ll have a psychological profile that’s both structured and full of gaps. Those gaps are features, not bugs. They’re spaces where your imagination can work, questions that will generate scenes and dialogue as you write.

I sometimes sketch a quick diagram showing how these five elements connect. Does the fatal flaw directly oppose the greatest strength? Does the subconscious fear make the conscious goal impossible? Where are the tensions? Where are the resonances?

You might discover that your initial concept for the character doesn’t quite fit the cards you drew. That’s okay. You can redraw if you want, but I’d encourage you to sit with the discomfort first. Sometimes the cards show you a more interesting version of your character than the one you thought you were creating.

This spread works equally well for protagonists, antagonists, and supporting characters. The more central the character is to your story, the more time you’ll want to spend developing each position. For minor characters, even just positions one and four might give you enough to make them memorable and consistent.

Beyond the Spread

The real value of using tarot for character development emerges over time, as you return to these cards throughout your writing process. When your character reaches a decision point in your plot, you can glance back at their subconscious fear and ask how it might be influencing their choice. When they succeed or fail, you can reference their greatest strength or fatal flaw.

Some writers keep their character spreads physically laid out near their workspace. Others photograph them or recreate them in digital documents. Find whatever method helps you reference these psychological touchstones without breaking your writing flow.

You might also discover that your character evolves in ways the spread didn’t predict. That’s fine. Tarot is a starting point for reflection, not a constraint on your creative freedom. If your character surprises you, let them. The cards opened a door to deeper characterization. Where you walk through that door is entirely up to you.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I need to know traditional tarot meanings to use this spread for character development?

Not at all. While understanding traditional interpretations can add depth, what matters most is your intuitive response to the imagery and symbolism. Look at what the card shows you and let your imagination connect it to your character’s psychology. Many successful writers using tarot for character work treat the cards primarily as visual brainstorming prompts rather than following strict divinatory meanings.

What if the cards I draw don’t seem to fit my character at all?

This disconnect is actually valuable. When cards feel misaligned with your initial character concept, they’re often revealing aspects you haven’t considered yet or pushing you toward a more interesting version of that character. Sit with the discomfort before redrawing. Sometimes the most compelling characters emerge when we let the cards challenge our assumptions rather than simply confirm what we already imagined.

Should I do this spread before I start writing or after I’ve already developed the character somewhat?

Either approach works, but the spread tends to be most generative when you have at least a basic concept of the character in mind. You need enough of a foundation to ask meaningful questions, but not so much detail that you’re inflexible. Think of it as a tool for the messy middle of character creation, when you know who they are on the surface but haven’t yet discovered what makes them truly complex.

Can I use this same spread for multiple characters in one story?

Absolutely. Running this spread for your protagonist, antagonist, and key supporting characters can reveal interesting dynamics and contrasts between them. You might discover that your hero’s greatest strength mirrors your antagonist’s fatal flaw, or that two characters share the same subconscious fear but respond to it in opposite ways. These connections create rich thematic resonance in your narrative.