Table of Contents

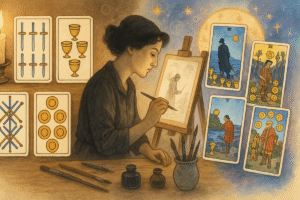

When you hold a tarot deck today, there’s a good chance you’re looking at artwork that traces back to one remarkable woman. Pamela Colman Smith, often called “Pixie” by her friends, created what would become the visual foundation for modern tarot. Yet for decades, her name was barely whispered in connection with the world’s most recognizable tarot deck.

I find it fascinating how history sometimes overlooks the very people who shape our cultural landscape. Smith’s story is one of artistic brilliance, spiritual exploration, and unfortunately, the kind of oversight that was all too common for women artists in the early 1900s.

The Early Years of an Artistic Spirit

Pamela Colman Smith was born in London in 1878, though her childhood was anything but conventional. Her family moved frequently between England, Jamaica, and New York, giving young Pixie exposure to diverse cultures and artistic traditions that would later influence her work in profound ways.

Perhaps this early exposure to different worlds helped shape her unique artistic vision. Smith’s childhood in Jamaica was particularly formative. She absorbed the island’s rich folklore, vibrant colors, and storytelling traditions. These elements would later emerge in her tarot illustrations, bringing a warmth and narrative depth that hadn’t been seen in earlier tarot designs.

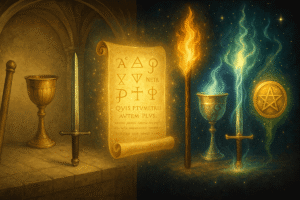

Her artistic education began at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where she studied under Arthur Wesley Dow. This training emphasized the importance of Japanese woodblock techniques and the power of simplified, symbolic imagery. Looking at Smith’s tarot cards today, you can see how this foundation influenced her approach to creating images that were both detailed and immediately readable.

A Creative Soul in Search of Expression

After her formal education, Smith moved in fascinating circles. She became involved with the theater, creating stage designs and costumes. This theatrical background shows up everywhere in her tarot work. Each card feels like a small stage, with characters positioned to tell their story at a glance.

Smith was also deeply involved in the suffrage movement and various spiritual communities. She attended séances, explored different religious traditions, and seemed genuinely curious about the mysteries of human experience. This spiritual seeking wasn’t just a hobby for her; it became central to how she approached her art.

What strikes me about Smith’s pre-tarot work is how she was already exploring themes of symbolism and storytelling. Her illustrations for various magazines and books showed a consistent interest in folklore, mythology, and the kind of archetypal imagery that would make her tarot cards so powerful.

The Fateful Meeting with A.E. Waite

Arthur Edward Waite was already an established figure in occult circles when he met Smith through their mutual involvement in the Golden Dawn, a secret society focused on magical and spiritual studies. Waite had ideas about creating a new tarot deck, one that would make the cards more accessible to ordinary people.

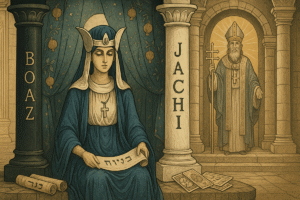

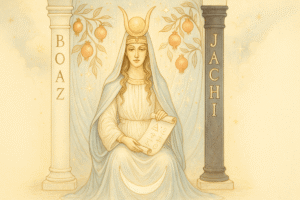

Previous tarot decks, particularly the minor arcana cards, had been quite simple. They typically showed just the suit symbols—five cups, seven swords, and so on—without any narrative scenes. Waite envisioned something different, and Smith had the artistic skills to make his vision reality.

Their collaboration began around 1909, and it’s worth noting that this was very much a partnership, even if history hasn’t always acknowledged it that way. Waite provided the symbolic framework and some general guidance, but Smith created every single image. She developed the visual language, chose the color palettes, and decided how each scene would unfold.

Revolutionizing Tarot Through Visual Storytelling

Smith’s greatest innovation was her decision to create fully illustrated scenes for all 78 cards. This might not sound groundbreaking today, but it completely transformed how people could interact with tarot. Instead of memorizing abstract meanings for numbered cards, readers could look at Smith’s illustrations and see stories unfolding.

Take the Three of Cups, for example. Rather than just showing three cup symbols, Smith painted three figures raising their cups in celebration. Suddenly, the card wasn’t just about the number three and the element of water. It was about friendship, community, shared joy. The image told the story.

Her artistic choices were remarkably sophisticated. Smith used color psychology, symbolic placement, and visual metaphors to layer meaning into each illustration. The way she depicted body language, facial expressions, and environmental details created cards that could be “read” on multiple levels.

I think what makes Smith’s work so enduring is how she balanced universal symbols with personal touches. Her figures feel like real people experiencing real emotions, not abstract representations of concepts. This human quality makes the cards feel relevant across different time periods and cultures.

The Forgotten Artist

Here’s where Smith’s story becomes somewhat heartbreaking. The deck was published in 1910 as the “Rider-Waite Tarot,” named after the publisher (Rider) and Waite. Smith’s name didn’t appear anywhere on the original deck or packaging. She was paid a flat fee for her work and received no royalties, despite creating what would become the most influential tarot imagery in history.

This erasure wasn’t uncommon for women artists of her era, but it’s particularly striking given how completely Smith’s vision shaped modern tarot. For decades, people referred to it as the Rider-Waite deck, with no acknowledgment of the artist who actually created the visual elements that made it special.

Smith continued creating art after the tarot project, but she never achieved the financial success her talent deserved. She converted to Catholicism later in life and moved back to England, where she lived quietly until her death in 1951. Many of her later works were religious in nature, showing a continued interest in spiritual themes.

Reclaiming Her Legacy

Fortunately, the tarot community has begun recognizing Smith’s contribution. Many publishers now call it the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, and some use “Smith-Waite” to emphasize her role. Collectors and historians have worked to piece together more details about her life and celebrate her artistic achievements.

Looking at Smith’s complete body of work, you can see consistent themes: a fascination with storytelling, an eye for symbolic detail, and a deep respect for folklore and spiritual traditions. Her tarot cards weren’t just commercial illustrations; they were the culmination of a lifetime spent exploring how images can convey meaning and emotion.

What’s particularly remarkable is how well her imagery has aged. Created over a century ago, these cards still speak to people across different cultures and backgrounds. That’s the mark of truly great art—it transcends its original context and continues to offer new insights to each generation of viewers.

The Artist’s Enduring Impact

Today, when someone picks up their first tarot deck, they’re likely encountering Pamela Colman Smith’s artistic vision, even if they don’t know her name. Her approach to visual storytelling has influenced countless other deck creators, and her understanding of symbolic imagery has shaped how we think about tarot as a whole.

Perhaps most importantly, Smith created art that invites contemplation. Her cards don’t just present information; they encourage viewers to look deeper, to consider multiple interpretations, to engage with the imagery on both intellectual and emotional levels. This reflective quality makes her work perfect for personal growth and self-exploration.

When I look at a Smith-illustrated card, I’m often surprised by details I hadn’t noticed before, or by new ways of interpreting familiar scenes. This depth and complexity ensure that her artwork remains fresh and relevant, even after multiple viewings.

Smith’s legacy reminds us that the most powerful art often comes from artists who combine technical skill with genuine curiosity about human experience. She wasn’t just illustrating tarot cards; she was creating windows into the human psyche, tools for reflection and understanding that continue to serve readers more than a century later.

Her story also serves as an important reminder about artistic recognition and the value of properly crediting creative work. While we can’t change how Smith was treated during her lifetime, we can ensure that future generations know her name and understand her contribution to both tarot and art history.

Pamela Colman Smith deserves to be remembered not just as the artist behind famous tarot cards, but as an innovative creator who understood the power of visual storytelling to illuminate the deepest aspects of human experience.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long did it take Pamela Colman Smith to create the tarot deck?

Smith completed all 78 card illustrations in just a few months during 1909. This remarkably short timeframe makes her achievement even more impressive when you consider the level of detail and symbolic complexity she incorporated into each card. She worked in pen and ink, likely with watercolor additions, though the original drawings have since been lost.

Did Pamela Colman Smith receive royalties for the tarot deck?

Unfortunately, no. Smith was paid only a flat fee for her work and received no royalties or ongoing compensation, despite creating what would become the most popular tarot deck in history. This was common practice for commissioned artwork at the time, particularly for women artists. Today, with over 100 million copies of her deck design in circulation worldwide, this lack of recognition and compensation stands as a stark reminder of how women’s creative contributions were undervalued.

Why was her name left off the deck for so long?

The deck was originally published as the Rider-Waite Tarot, named after the publisher William Rider and the person who commissioned it, Arthur Edward Waite. Smith’s contribution was viewed primarily as commercial illustration work, and her role wasn’t prominently acknowledged on the packaging. It wasn’t until the 1970s and beyond that tarot scholars and communities began advocating for her recognition, leading to names like Rider-Waite-Smith, Waite-Smith, or Smith-Waite being used today. Her serpentine monogram signature, which appears on each card, was the only indication of her authorship for decades.

What happened to the original tarot card artwork?

The original drawings have disappeared and their current location remains unknown. When Smith died in 1951, her belongings were sold at auction to pay off her debts. Some of her other artworks survive in museum collections, but the tarot originals have never been definitively located, adding another layer of mystery to her already enigmatic story.