Table of Contents

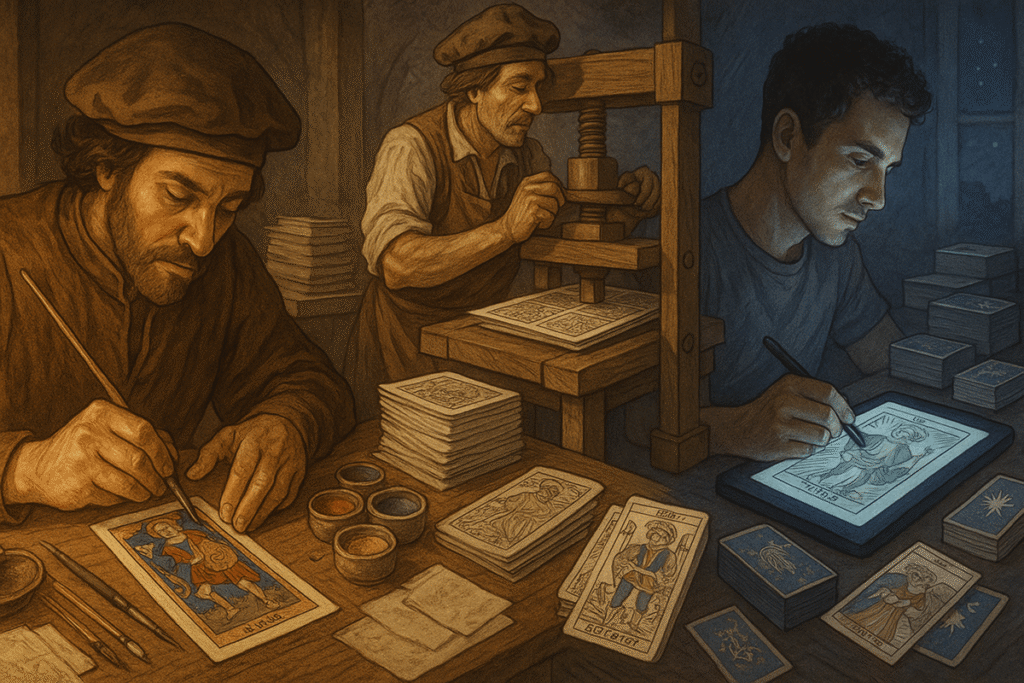

When I first started collecting tarot decks, I never really thought about how they were made. I just appreciated the art, the symbolism, the feel of the cards in my hands. But then one day, while examining a reproduction of an antique Tarot de Marseille, I noticed the slightly uneven lines and the layered colors that spoke of a completely different production process. It made me wonder about the journey these cards took from luxury items locked away in noble households to the accessible, diverse decks we can order online today.

The story of tarot card printing is actually the story of printing itself, woven together with art history, social change, and the democratization of images. It’s a journey worth exploring, even if you’ve never thought much about the technical side of your favorite deck.

The Earliest Tarot Cards Were Not Printed At All

In the beginning, there was no printing. The very first tarot cards, created in 15th century Italy, were painted by hand. These weren’t the mystical divination tools we think of today. They were called carte da trionfi, or triumph cards, and they were essentially luxury playing cards commissioned by wealthy families like the Visconti and Sforza dynasties of Milan.

Each card was a miniature artwork. Skilled painters applied tempera and gold leaf to heavy paper or thin sheets of wood, creating images of elaborate allegories, courtly figures, and symbolic scenes. The Visconti-Sforza deck, one of the oldest surviving examples, shows this exquisite craftsmanship. Every detail was deliberate, from the folds in the clothing to the expressions on faces.

These hand-painted decks took weeks or months to complete, which meant only the very wealthy could afford them. A tarot deck was as much a status symbol as a jeweled necklace or a thoroughbred horse. The cards served primarily as entertainment for nobles, used in a game called tarocchi that was popular at Italian courts.

Perhaps what’s most striking about these early decks is their individuality. Because each was painted separately, no two decks were exactly alike. The artist’s hand, their particular style and interpretation, made every deck unique. This stands in such contrast to our modern expectation that cards should be identical, reproducible, standardized.

Woodblock Printing Brings Tarot to the People

Everything changed with the woodblock. By the late 15th and early 16th centuries, woodblock printing had become well established across Europe for producing books, religious images, and playing cards. The process was laborious but revolutionary. An artisan would carve a design into a block of wood, cutting away everything except the lines and shapes that should appear on the final print. Ink was applied to the raised surfaces, and paper was pressed against the block.

For tarot cards, this usually meant creating separate blocks for the outline and for each color. A printer might use three, four, or five different blocks for a single card, carefully aligning each one to build up the layers of color. The technique was called chiaroscuro when it involved multiple color blocks, though simpler versions used just black outlines that were hand-colored afterward.

The Tarot de Marseille emerged from this era and this technology. Developed in the 17th century, primarily in France but drawing on Italian traditions, the Marseille-style deck became the standard template. Its bold, somewhat crude imagery was perfectly suited to woodblock production. The designs were clear, the symbolism was direct, and the cards could be produced in quantities that earlier generations couldn’t have imagined.

I think there’s something about the Marseille aesthetic that still resonates today. Those thick black outlines, the flat areas of color, the almost naive quality of the figures. It looks ancient and authentic precisely because it bears the marks of its production method. Modern reproductions often try to capture that woodblock feel, even when they’re printed digitally.

Woodblock printing democratized tarot in a real sense. Cards became affordable enough that middle-class families could own a deck. Tarot spread beyond Italy into France, Switzerland, and eventually across Europe. The game remained popular, but something else was happening too. People began using the cards for cartomancy, for fortune-telling. When more people have access to something, new uses emerge.

The Lithographic Revolution and Victorian Innovation

The 19th century brought lithography, and with it, another transformation. Lithography worked on a completely different principle than woodblock printing. Instead of carving into wood, an artist drew directly onto a smooth limestone surface with a greasy crayon. The stone was then treated with chemicals so that ink would stick only to the drawn areas. Each stone could produce thousands of impressions, and the detail possible was extraordinary.

For tarot cards, lithography meant finer lines, more subtle shading, and greater artistic freedom. It also meant color could be added more easily through chromolithography, which used multiple stones, each carrying a different color. The results could be stunningly beautiful and far more nuanced than anything possible with woodblocks.

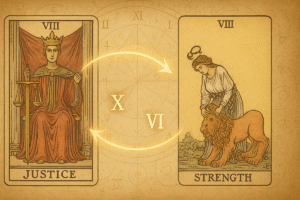

This is when we start to see the emergence of what I’d call “artist-designed” tarot decks. The most famous, of course, is the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, created in 1909. Pamela Colman Smith’s watercolor illustrations were reproduced through lithographic printing, and her innovative decision to illustrate all 78 cards, including the minor arcana, set a new standard that most modern decks still follow.

The Victorian era was also when tarot shifted decisively toward occult and esoteric purposes in the English-speaking world. Groups like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn developed elaborate symbolic systems based on tarot, and new decks were designed specifically for mystical study rather than gaming. The printing technology available made it feasible to produce these specialized decks for niche audiences.

What strikes me about this period is how printing technology and spiritual movements evolved together. Would the occult tarot revival have happened without lithography making it practical to produce and distribute these new interpretations? It’s hard to say, but the timing seems more than coincidental.

Offset Printing and the Modern Era

The 20th century brought offset lithography, which became the dominant commercial printing method and remains so today for many applications. Offset printing transfers an image from a metal plate to a rubber blanket, then to the printing surface. It’s fast, it’s economical for large runs, and it produces consistent, high-quality results.

For decades, this was how virtually all tarot decks were produced. A deck designer would create artwork, it would be photographed or scanned, plates would be made, and thousands of identical decks would roll off the presses. The U.S. Games Systems company, which owns the rights to the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, used offset printing to make that deck the bestselling tarot in the world.

The economics of offset printing shaped what decks got made. Because the setup costs were high, publishers needed to be confident they could sell thousands of copies. This meant safe bets, proven designs, variations on established themes. Independent artists with unconventional visions had limited options unless they could find a publisher willing to take a risk.

The card stock improved dramatically during this era too. Modern casino-quality cardboard with plastic coating, the kind that shuffles smoothly and holds up to repeated use, became standard. Perhaps these technical improvements seem mundane compared to artistic innovation, but they matter. A deck that falls apart after a few months of use doesn’t serve anyone well.

The Digital Age and Print on Demand

And now we’re here, in the digital era, and honestly, it’s a wild time to be interested in tarot. Desktop publishing software, digital illustration tools, and especially print-on-demand services have completely transformed who can create and sell a tarot deck.

Print-on-demand is the real game changer. Companies like MakePlayingCards or PrintNinja will print a single deck or a small batch without requiring a minimum order of thousands. An artist can design a deck on their computer, upload the files, and have physical cards in their hands within weeks. No need to invest tens of thousands of dollars upfront. No need to convince a traditional publisher that the concept is marketable.

This has led to an absolute explosion of indie tarot decks. Crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter have become the new marketplace, where creators pitch their visions directly to potential buyers. Some of these campaigns raise hundreds of thousands of dollars. The diversity of styles, themes, and approaches is staggering. There are tarot decks based on literary works, video games, specific cultural traditions, political movements, personal trauma, ecological themes, queer identity. The list goes on.

I sometimes browse these projects just to see what people are creating. The creativity is inspiring, but I also notice something else. The quality varies wildly. Without the gatekeeping function that traditional publishers provided, both good and bad, there’s no quality control. Some decks are beautifully conceived and executed. Others feel rushed or poorly thought through. The barrier to entry is so low that anyone can make a deck, which is both wonderful and occasionally problematic.

Digital printing technology has also enabled personalization and variation in ways that weren’t possible before. Some artists offer custom cards or decks tailored to individual buyers. Others release multiple versions of the same deck with different color schemes or border treatments. The rigid standardization of the offset era is giving way to something more fluid.

What All This History Means for How We Use Tarot Today

Thinking about this progression from hand-painted luxury to digital accessibility, I find myself reflecting on what’s been gained and lost along the way. We’ve gained access, certainly. Anyone can own multiple decks now, can choose from thousands of options, can even create their own if they’re so inclined. The images and ideas are no longer locked behind walls of privilege or economic barriers.

But perhaps we’ve also lost something of the reverence that came with rarity. When a deck took months to paint and cost a small fortune, it was treasured differently. The relationship between user and tool was different. I’m not saying we should go back to that, obviously. Democratization is good. But it’s worth acknowledging that abundance changes the nature of the relationship.

The history of tarot printing also reminds us that these cards have always been products of their technological moment. The bold simplicity of the Marseille was perfect for woodblocks. The ethereal quality of Smith’s art suited lithography. The current explosion of conceptual and thematic diversity is only possible because of digital tools and on-demand printing. Each era’s technology shapes not just how cards are made but what kinds of decks are conceivable.

Where does this journey go next? Will AI-generated imagery become common in tarot decks, and how will that change things? Will augmented reality create hybrid physical and digital experiences? It’s hard to predict, but if history teaches us anything, it’s that tarot will adapt and evolve with whatever comes next. The cards have survived five centuries of technological and cultural change. They’ll survive whatever the future brings.

For now, I’m just grateful to live in a time when I can hold a beautifully printed deck in my hands, knowing that somewhere, someone is designing the next innovative interpretation of these archetypal images. The tools have changed, but the human desire to create meaning through symbols continues, unbroken, from those first hand-painted cards in Milan to whatever gets uploaded to a print-on-demand service tomorrow.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why were early hand-painted tarot cards so expensive?

Creating hand-painted tarot cards required skilled artisans who spent weeks or months applying tempera and gold leaf to each individual card, making them luxury items accessible only to wealthy Italian families. The labor-intensive nature of the work, combined with the use of precious materials like gold leaf, meant each deck was essentially a commission piece. Unlike today’s mass-produced cards, no two hand-painted decks were identical, which added to their value as both functional game pieces and status symbols in Renaissance courts.

What made woodblock printing revolutionary for tarot cards?

Woodblock printing democratized tarot by making cards affordable enough for middle-class families to own, fundamentally changing who could access them. The technique involved carving designs into wood blocks and using multiple blocks for different colors, which allowed printers to produce hundreds of identical cards rather than painting each one individually. This shift from exclusive luxury items to accessible entertainment pieces happened primarily in the 17th century with decks like the Tarot de Marseille, whose bold, simple designs were perfectly suited to the woodblock method’s capabilities.

How did lithography improve tarot card quality?

Lithography revolutionized colored impressions through chromolithographs and introduced a cheaper printing method compared to copper engraving. The process allowed artists to draw directly onto limestone, producing far more detail and subtle shading than woodblocks could achieve. This technology made it possible to reproduce delicate artwork like Pamela Colman Smith’s watercolor illustrations for the 1909 Rider-Waite-Smith deck with unprecedented fidelity, including the innovative decision to fully illustrate all 78 cards rather than just the major arcana.

Why has there been an explosion of indie tarot decks recently?

Print-on-demand services have eliminated the traditional barriers to deck creation by removing minimum order requirements that once forced artists to invest tens of thousands of dollars upfront. Creators can now design a deck digitally, upload files, and receive physical cards within weeks without needing publisher approval. Combined with crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter that connect artists directly with buyers, this has enabled unprecedented diversity in themes, styles, and perspectives, from decks exploring specific cultural traditions to those addressing contemporary social movements.