Table of Contents

When you think about tarot cards today, you probably imagine mysterious symbols, deep introspection, and perhaps a dimly lit room where someone asks profound questions about their life path. But here’s something that might surprise you: for most of tarot’s history, these decorated cards were nothing more than a parlor game. The transformation of tarot into a tool for personal reflection and spiritual exploration happened remarkably recently, and it happened almost entirely in France during the 1800s.

I find this story fascinating because it shows how creative minds can take something ordinary and reimagine it completely. The French occultists of the nineteenth century didn’t just add new interpretations to tarot. They essentially rebuilt it from the ground up, layering it with symbolism drawn from Kabbalah, alchemy, astrology, and ancient Egyptian mysteries. Whether these connections were historically accurate matters less than the fact that they captured imaginations and created a framework that still influences how people approach tarot today.

The Playing Cards That Became Something More

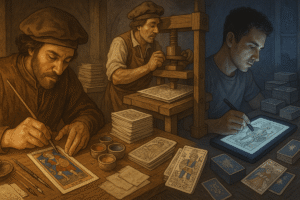

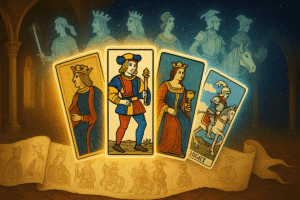

Tarot started as a card game in fifteenth-century Italy. The earliest decks were commissioned by wealthy families, hand painted and gilded, more art objects than gaming tools. By the 1700s, tarot had spread across Europe, particularly popular in France where it was called “tarot” or sometimes “tarock” in different regions.

These weren’t mystical objects. People used them to play trick-taking games, wagering small amounts and passing time. The imagery on the cards was allegorical, sure, depicting virtues, vices, and scenes from everyday life or classical mythology. But nobody was consulting them about their future or using them for spiritual guidance. They were entertainment, pure and simple.

Then something shifted in France during the Enlightenment and its aftermath. As traditional religious authority faced questioning, people became hungry for alternative ways of understanding the world and themselves. Secret societies flourished. Interest in alchemy, astrology, and “hidden knowledge” grew among educated circles. The stage was set for someone to look at those old gaming cards and see something entirely different.

Etteilla Sees What Others Missed

Jean-Baptiste Alliette was a Parisian seed merchant and wig maker who became absolutely convinced that tarot held ancient wisdom. Working in the 1770s and 1780s, he reversed his name to create the pseudonym “Etteilla” and began publishing books about cartomancy, the practice of reading cards for insight.

What made Etteilla different was his commitment to the idea. He didn’t just use existing tarot decks for divination. He redesigned them entirely. In 1789, he published what many consider the first tarot deck created specifically for esoteric purposes rather than gaming. His “Grand Etteilla” deck reworked the traditional images and added Egyptian motifs, based on his belief that tarot originated in ancient Egypt and contained the lost wisdom of that civilization.

Was there any historical evidence for this Egyptian connection? Not really, no. But that didn’t matter much to Etteilla or his followers. The idea was appealing, romantic, and gave tarot a sense of gravitas and ancient authority. He created detailed systems for interpreting the cards, assigning specific meanings to each one and establishing methods for laying them out in spreads.

I think Etteilla succeeded because he offered people something they wanted: a structured way to explore questions about their lives. His system gave tarot a seriousness it hadn’t possessed before. Instead of a game, it became a tool for contemplation and self examination. Whether you believe in divination or not, you have to admit there’s value in having prompts that make you think deeply about your circumstances and choices.

His influence spread through France and beyond. Students learned his methods. Other cartomancers built on his work. But perhaps his greatest contribution was simply demonstrating that tarot could be more than entertainment. He opened a door that others would walk through, expanding the possibilities even further.

Eliphas Lévi Builds the Bridge

If Etteilla gave tarot an esoteric identity, Eliphas Lévi gave it a complete cosmological framework. Born Alphonse Louis Constant in 1810, Lévi started as a seminarian before leaving the church and eventually becoming one of the most influential occult writers of the nineteenth century. His work in the 1850s and 1860s fundamentally reshaped how educated occultists thought about tarot.

Lévi’s big insight, or perhaps invention, was connecting tarot’s Major Arcana to the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet and the paths on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. This wasn’t just adding a layer of symbolism. It was integrating tarot into a much larger system of Western esoteric thought that included Jewish mysticism, Hermeticism, alchemy, and astrology.

In books like “Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie” (Dogma and Ritual of High Magic), Lévi presented tarot as a kind of universal key to hidden knowledge. Each card became a meditation on cosmic principles. The Fool wasn’t just a wanderer; it represented the divine spirit before manifestation. The Magician embodied the principle of active will. The High Priestess symbolized intuitive wisdom and hidden knowledge.

Was this what the original Italian artists intended when they painted these images? Almost certainly not. But Lévi wasn’t concerned with historical accuracy as much as creating a coherent symbolic system. And it worked, brilliantly. His framework gave serious occultists a reason to study tarot alongside other esoteric subjects.

What strikes me about Lévi is how he elevated tarot within occult circles. Before him, cartomancy had a somewhat dubious reputation, associated with fortune tellers working for coins at fairs. Lévi made tarot intellectual, even scholarly. He wrote in dense, allusive prose that required real effort to understand. Studying his work became a mark of serious engagement with occult philosophy rather than mere curiosity about fortune telling.

The Symbolic Language Takes Shape

Both Etteilla and Lévi were doing something similar, though their approaches differed. They were creating a symbolic language that people could use to think about their inner lives and spiritual questions. The specific correspondences they proposed, whether Egyptian gods or Kabbalistic paths, mattered less than the fact that they made tarot into a coherent system.

This is perhaps what makes their work so enduring. The details have been debated, revised, and expanded by countless occultists since. The Golden Dawn magical order, Arthur Edward Waite, Aleister Crowley, and many others built on the French foundation, each adding their own interpretations. But that foundation remains remarkably stable.

When you look at a modern tarot deck, you’re seeing the result of these nineteenth-century innovations. The idea that each card carries multiple layers of meaning, that the images invite personal reflection, that the deck as a whole represents a journey or system of understanding yourself and the world… all of this comes from the French occult revival.

Personal Reflection Rather Than Prediction

Here’s what I find most interesting about this history. The French occultists transformed tarot, but they also, perhaps inadvertently, created a tool that works regardless of whether you believe in any of their mystical theories. You don’t need to accept that tarot came from Egypt or that it corresponds to Kabbalistic paths to find value in the cards.

Modern approaches often emphasize tarot as a mirror for self reflection. When you draw a card and contemplate its imagery and traditional meanings, you’re really examining your own thoughts, feelings, and circumstances through a particular lens. The card becomes a prompt: What does The Tower’s imagery of sudden change make me think about in my current situation? How does The Star’s symbolism of hope speak to what I’m experiencing?

This reflective use aligns beautifully with the creative legacy of Etteilla and Lévi. They weren’t really recovering ancient wisdom; they were inventing new frameworks for thinking about human experience. And that invention has proven remarkably durable precisely because it invites ongoing interpretation and personal meaning making rather than demanding adherence to fixed predictions.

The Evolution Continues

The story of French occultism and tarot doesn’t end in the nineteenth century, of course. Their innovations spread internationally, influenced countless deck designers and writers, and ultimately shaped the modern tarot revival that began in the 1960s and 70s. Today’s explosion of diverse tarot decks, from minimalist to maximalist, feminist to fantastical, all stand on that French foundation.

What Etteilla and Lévi did was give permission for imagination and creativity. They showed that you could take a cultural artifact, reimagine its purpose completely, and create something meaningful in the process. The historical accuracy of their claims about Egyptian mysteries or Kabbalistic connections is honestly beside the point. What matters is that they saw potential where others saw only playing cards, and they built systems that helped people explore questions about themselves and their lives.

Perhaps that’s the real magic of tarot: not predicting the future, but providing a structured way to think about the present. The French occultists of the 1800s gave us that gift, transforming a simple card game into a rich symbolic system that continues to invite reflection and self exploration. Whether you approach tarot as spiritual practice, psychological tool, or historical curiosity, you’re participating in a tradition that began with those imaginative French thinkers who dared to see something more in a deck of cards.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Etteilla and Lévi actually believe tarot came from ancient Egypt?

Yes, both genuinely believed in tarot’s Egyptian origins, though there’s no historical evidence supporting this claim. Etteilla was convinced tarot contained ancient wisdom from Egypt’s Book of Thoth, while Lévi claimed the cards “came to us from Egypt passing through Judea.” This Egyptian theory was popular among occultists at the time, inspired by Napoleon’s Egyptian campaigns and the era’s fascination with ancient mysteries. Modern scholarship has confirmed tarot actually originated in fifteenth century Italy as playing cards, but the Egyptian mythology these thinkers created proved far more influential than historical accuracy.

Why did Eliphas Lévi criticize Etteilla if they were both creating esoteric tarot systems?

Lévi’s criticism of Etteilla was largely rooted in class snobbery and intellectual elitism. He dismissed Etteilla as an “illuminated hairdresser” with clumsy writing who commercialized tarot for “vulgar” fortune telling rather than serious spiritual study. Lévi positioned tarot as a tool for high ceremonial magic and scholarly occultism, while Etteilla openly worked as a professional card reader serving everyday clients. This tension reflected broader debates in occult circles about whether tarot should be an academic pursuit or a practical divination tool, with Lévi favoring intellectual respectability over Etteilla’s populist approach.

Can you use tarot today without believing in the Kabbalistic or Egyptian theories these occultists created?

Absolutely. The symbolic frameworks Etteilla and Lévi built, while historically inaccurate, created a rich language for self reflection that works regardless of whether you accept their mystical theories. Modern approaches often treat tarot as a psychological mirror, where the imagery and traditional meanings prompt questions about your current circumstances rather than revealing ancient secrets or predicting futures. What these French occultists really invented was a structured system for contemplating life’s questions, and that system remains valuable whether you view it through an esoteric lens or simply as prompts for introspection and personal insight.