Table of Contents

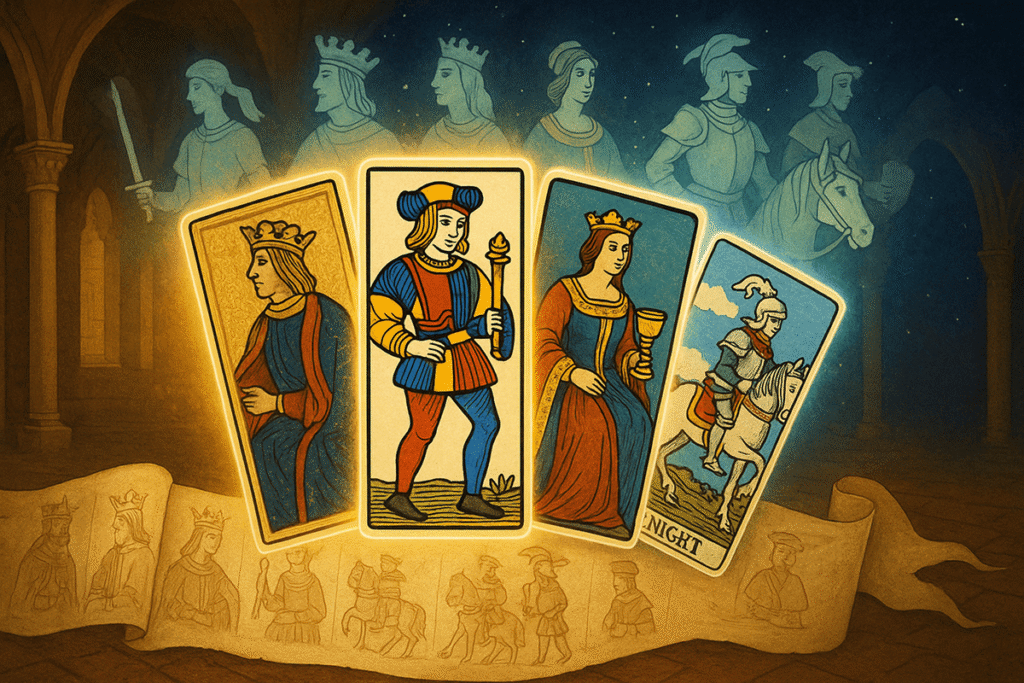

The court cards have always felt like the most human part of the tarot deck to me. Unlike the abstract symbolism of the Major Arcana or the elemental simplicity of the numbered suits, these figures stare back at us with distinct personalities and roles. They represent people, archetypes, and aspects of ourselves that we encounter in daily life. But their journey from Renaissance Italy to the decks we use today is more complex and fascinating than most readers realize.

When I first started exploring the history of tarot, I assumed the court cards had always been standardized. Four suits, each with a King, Queen, Knight, and Page. Simple, right? What I discovered instead was a rich tapestry of variations, experiments, and gradual standardization that took centuries to fully develop. The story of these cards reveals much about changing social hierarchies, artistic innovation, and the slow evolution of esoteric traditions.

The Italian Origins and Early Variations

Tarot emerged in Northern Italy during the early 15th century, though pinpointing an exact origin remains challenging for historians. The earliest surviving examples, particularly the Visconti-Sforza decks created for the ruling families of Milan, offer us a window into how these cards first appeared. These hand-painted treasures weren’t created for divination as we understand it today. They were luxury items, status symbols that demonstrated wealth and artistic patronage.

What strikes me most about these early decks is their inconsistency. The Visconti-Sforza tarot sometimes included additional court figures beyond what we now consider standard. Some versions featured female knights, or damigelle, alongside their male counterparts. Others experimented with multiple pages or additional ranked figures. This wasn’t carelessness or confusion. It reflected the reality of Italian court life, where hierarchies were complex and roles could be quite fluid depending on the specific household or region.

The standard playing card decks of the time, which tarot was based upon, typically featured only three court cards per suit. Adding a fourth figure, the Knight, was one of tarot’s distinctive innovations. This created a more elaborate hierarchy that perhaps better reflected the layered social structures of Renaissance nobility. Yet even this wasn’t immediately standardized across all tarot production.

The Gradual Path to Standardization

By the 16th century, tarot production had spread beyond Milan to other Italian regions and into France. Each area developed its own preferences and conventions. The Tarot de Marseille tradition, which emerged in France and became enormously influential, eventually settled on the King, Queen, Knight, and Page structure we recognize today. But this standardization happened gradually, almost accidentally, as certain deck designs proved more popular or practical for card makers to reproduce.

I think it’s worth noting that standardization was driven as much by economic factors as artistic ones. Hand-painted decks could accommodate variations and experimentation, but as woodblock printing and later copper engraving made mass production possible, manufacturers needed consistent templates. Creating four court cards per suit in four suits meant producing sixteen distinct designs, which was already a significant undertaking for early printers. Adding extra figures would have increased costs and complexity.

The symbolic associations we attach to each court rank also developed over time. Early court cards were largely decorative, with minimal symbolic distinction beyond their obvious hierarchical positions. The deep personality traits and elemental correspondences that modern tarot readers associate with these figures came much later, primarily through the work of occultists in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Gender Representation and Social Hierarchy

The presence of both Kings and Queens in tarot court cards reflects something interesting about how power was understood in Renaissance Europe. Unlike many playing card traditions that featured only male figures, tarot acknowledged feminine authority through the Queen cards. This wasn’t necessarily progressive by modern standards, but it did create space for exploring different aspects of power and personality.

The female knights, or damigelle, that appeared in some early Italian decks raise fascinating questions. Were they reflecting real women who held positions of authority? Were they simply artistic flourishes? Or did they represent something more symbolic about the nature of action and courage that transcended strict gender roles? The historical record doesn’t give us definitive answers, and perhaps that ambiguity is itself meaningful.

As tarot evolved, the gendered pairs within each suit came to represent complementary energies. The King and Queen of any suit weren’t just husband and wife in a literal sense. They embodied different approaches to the suit’s element. A King might represent external action and authority, while a Queen suggested internal mastery and nurturing power. These interpretations deepened over centuries as tarot moved from game to spiritual tool.

The Knights and Pages as Bridges

The Knight and Page positions occupy interesting middle ground in the court hierarchy. Knights represent action, movement, and the pursuit of goals. They’re dynamic figures, often depicted on horseback, suggesting transition and change. Pages, meanwhile, stand as messengers and students, the youngest or least experienced members of the court but full of potential and curiosity.

In some tarot traditions, particularly those influenced by English occultism, the Page is renamed the Princess or sometimes the Knave. These variations reflect different cultural contexts and interpretive frameworks. The Thoth tarot designed by Aleister Crowley with artist Lady Frieda Harris restructured the courts entirely, creating Princes and Princesses with complex elemental attributions that differ from traditional systems.

What I find compelling about the Knight and Page cards is their quality of incompleteness. They’re not fully established in their power like the King and Queen. They’re learning, questing, making mistakes. When these cards appear in a reading context, they often point toward processes of growth and development rather than fixed states. This gives them a particularly rich psychological dimension for personal reflection.

From Playing Cards to Spiritual Tools

The transformation of tarot from a gaming device to a tool for self-reflection and spiritual exploration fundamentally changed how the court cards were understood. In the 18th century, figures like Antoine Court de Gébelin began publishing theories about tarot’s ancient mystical origins. While many of these theories have been thoroughly debunked by historians, they inspired generations of occultists who developed elaborate symbolic systems around the cards.

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an influential magical society active in late 19th century Britain, created detailed correspondences linking each court card to astrological signs, elements, and personality types. Arthur Edward Waite and artist Pamela Colman Smith, both connected to the Golden Dawn, produced the Rider-Waite-Smith deck in 1909, which remains the most popular tarot design today. Their court cards feature detailed scenes and symbols that invite interpretation and reflection.

This shift toward seeing court cards as psychological archetypes rather than mere game pieces opened new possibilities. Each figure could represent an aspect of ourselves, a person in our lives, or a particular energy or approach we might adopt in a situation. This psychological framing makes the cards feel relevant and accessible even to those who don’t subscribe to any particular spiritual system.

Modern Interpretations and Continuing Evolution

Contemporary tarot deck designers continue to experiment with court card structures and symbolism. Some decks replace traditional royal hierarchies with more egalitarian structures. Others explore different cultural frameworks entirely, moving beyond European aristocratic models. The important thing, I think, is that the evolution hasn’t stopped.

When working with court cards today, whether in self-reflection practices or as prompts for journaling and personal growth, understanding their historical journey enriches our relationship with them. These aren’t fixed symbols handed down from ancient wisdom traditions. They’re living images that have adapted and changed across six centuries, shaped by artists, printers, occultists, and everyday users.

The question “What does this court card mean?” becomes less about memorizing a fixed definition and more about entering into dialogue with centuries of accumulated imagery and interpretation. The King of Cups in a 15th century Italian deck wasn’t designed to represent emotional mastery or mature feeling, but that’s one lens through which we might view him today. Both perspectives are valid, and understanding the historical context helps us hold our modern interpretations more lightly, with greater nuance.

Reflections on Rank and Personal Growth

Perhaps the most valuable insight from studying the evolution of tarot court cards is recognizing that hierarchies of experience and mastery exist, but they’re not static or absolute. The progression from Page to Knight to Queen to King isn’t a simple ladder we climb once and complete. In different areas of our lives, we embody different ranks at different times.

You might be the Queen of your professional domain while simultaneously being the Page of a new hobby you’re exploring. Someone can demonstrate the decisive action of a Knight in one situation while needing the receptive wisdom of a Queen in another. The court cards, with their long history of variation and gradual standardization, remind us that these categories are useful frameworks rather than rigid boxes.

When I sit with these cards now, I sometimes try to imagine the artisan in 15th century Milan carefully painting a female knight onto vellum, or the French printer in the 1600s deciding which court card designs would be easiest to reproduce. Their practical choices and artistic experiments shaped the symbolic vocabulary we still use today. That continuity across time feels meaningful, a reminder that our own interpretations and innovations are part of an ongoing conversation rather than a final answer.

The evolution of court cards continues in each deck that reimagines them, and in each person who sits down to reflect on what these figures might represent in their own life journey.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did some early Italian decks include female knights and pages?

The Cary-Yale Visconti deck featured six court cards per suit, including female knights (damigelle) and female pages alongside their male counterparts. Historians suggest this unique structure may have reflected the deck being commissioned for a woman, possibly Bianca Maria Visconti herself, or represented a more nuanced view of courtly roles before standardization took hold. These additional figures demonstrate how flexible the early tarot format was before economic and practical printing considerations narrowed the options.

When did the four court card structure become the standard?

The earliest decks identified as tarot with a fifth suit of trumps were created in northern Italy around the 1420s, with the Visconti-Sforza decks from the 1450s being the oldest surviving examples. The standardization to exactly four court cards per suit happened gradually through the 15th and 16th centuries, driven largely by printing technology. Mass production through woodblock printing and copper engraving made consistent templates necessary, and the four-figure hierarchy (King, Queen, Knight, Page) proved most practical to reproduce across regions.

Do court cards have to represent actual people in readings?

Court cards can represent several things depending on context. They might symbolize specific individuals in your life, aspects of your own personality, energies you’re projecting or need to embody, or even phases of personal development. For reflective practices, consider what qualities each court figure might be inviting you to explore within yourself rather than seeking to identify them as specific external people. The King of Cups might prompt reflection on emotional maturity, while the Page of Wands could suggest curiosity about new creative directions.