Table of Contents

When I first started exploring the history behind tarot cards, I expected to trace them back to medieval Europe, maybe France or Italy. What I didn’t expect was to find myself reading about Egyptian sultanates, polo matches, and intricate hand-painted cards that predated the Renaissance by decades. The Mamluk cards of 14th-century Egypt turned out to be far more fascinating than I’d anticipated, and they’re arguably the most important ancestors of what we now recognize as the Minor Arcana in tarot decks.

The story of how these Islamic playing cards made their way from Cairo to Venice, transforming along the journey, reveals something unexpected about cultural exchange during a time we often imagine as isolated and insular. I think understanding this history adds a dimension to tarot that many people miss entirely.

The Mamluk Sultanate and the Birth of a Card System

The Mamluk Sultanate controlled Egypt and parts of the Levant during the 13th and 14th centuries. This was a period of relative prosperity and cultural flowering, despite the constant military pressures the sultanate faced. The Mamluks themselves were originally slave soldiers, many of them Turkic or Circassian, who had risen to power and established their own dynasty. Their court culture blended influences from across the Islamic world, from Persia to North Africa.

It was within this context that the earliest known Mamluk playing cards appeared, probably sometime in the 14th century. These weren’t cards as we might imagine them today. They were hand-painted works of art, created on thin layers of paperboard or pasteboard, often featuring elaborate geometric designs and Arabic calligraphy. The craftsmanship was remarkable, though I suspect only the wealthy could afford such luxury items.

What made these cards particularly significant was their structure. The Mamluk deck consisted of 52 cards divided into four suits. Each suit contained ten numbered cards and three court cards. Perhaps this sounds familiar? It should, because this basic architecture would eventually become the foundation for both modern playing cards and the Minor Arcana of tarot.

Four Suits That Crossed Continents

The four Mamluk suits were cups, swords, coins, and polo sticks. Yes, polo sticks. This detail always catches people off guard when they first encounter it. Polo was an enormously popular sport among the Mamluk elite, imported from Persia where it had been played for centuries. The inclusion of polo sticks as a suit symbol reflected the aristocratic nature of the game and the cards themselves.

Each of these suits carried symbolic weight. Cups might have represented the merchant class or perhaps spiritual sustenance. Swords clearly evoked the military, which makes sense given the Mamluk origins as warrior-rulers. Coins symbolized wealth and trade, the economic foundations of the sultanate. And those polo sticks? They represented the leisure and privilege of the ruling class, the equipment of kings and generals at play.

When these cards eventually reached Europe, probably through trade routes connecting Egypt with Italian port cities like Venice and Genoa, the suit symbols underwent a transformation. Cups remained cups. Swords stayed swords. Coins continued as coins. But polo sticks presented a problem. Europeans didn’t play polo. The game was unknown to them. So the symbol was reinterpreted, possibly as batons or wands or staves, something more familiar to the European context.

I find it interesting that three of the four suits required no translation at all. They were universal enough in their symbolism that Italian card makers simply adopted them wholesale. Only the polo sticks needed adaptation, eventually becoming the batons or wands we see in Italian suited decks today.

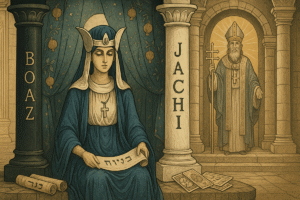

Court Cards Without Faces

One striking feature of Mamluk cards was the absence of human figures on the court cards. Islamic artistic tradition, particularly in religious contexts, often avoided representational imagery of people or animals. While this prohibition was interpreted with varying degrees of strictness across different times and places, Mamluk card designers chose to honor it.

Instead of depicting kings, governors, and deputies (the three ranks of Mamluk court cards), the cards featured the titles written in ornate calligraphy, surrounded by elaborate geometric and floral patterns. The word for the rank would appear, beautifully rendered, but no human face or form accompanied it. This created cards that were visually stunning but quite different from what would emerge later in Europe.

When Italian craftsmen began producing their own versions of these cards in the 15th century, they had no such restrictions. The court cards quickly became populated with human figures: kings on thrones, knights on horseback, pages or knaves standing ready to serve. This shift toward figurative imagery would become one of the defining characteristics of European card design, and eventually of tarot iconography.

The transformation raises questions about how much meaning was lost or changed in the translation. The abstract, text-based Mamluk court cards perhaps suggested something more conceptual, while the Italian figurative versions made the hierarchy more literal and visual. Both approaches work, but they reflect fundamentally different aesthetic and cultural values.

The Journey Into Europe

The exact route by which Mamluk cards entered Europe remains somewhat mysterious. We know that trade between Mamluk Egypt and Italian city-states was robust throughout the 14th century. Venetian and Genoese merchants maintained trading posts in Alexandria and other Mediterranean ports. Goods, ideas, and cultural artifacts flowed in both directions.

Playing cards probably arrived as curiosities at first, luxury items that caught the attention of wealthy Italian patrons. By the late 14th century, references to playing cards begin appearing in European documents. A 1377 manuscript by a German monk named Johannes describes card games being played in various European locations, suggesting that cards had already spread beyond Italy by that point.

Italian card makers, recognizing a market opportunity, began producing their own versions. They kept the four-suit structure and the division between numbered cards and court cards. The suits were adapted, as I mentioned, with cups, swords, coins, and batons becoming the standard Italian configuration. These Italian suited cards would serve as the direct template for what came next.

And what came next, of course, was tarot. Sometime in the mid-15th century, probably in northern Italy, someone had the idea of adding a fifth suit of allegorical trump cards to the existing four-suit deck. These trumps, numbered and illustrated with symbolic imagery, were initially created for a new game. They would eventually evolve into the Major Arcana, the most recognizable part of tarot iconography today.

But the Minor Arcana, those four suits of numbered and court cards, remained essentially unchanged from their Mamluk origins. The structure was too elegant, too functional, to require reinvention.

What This History Means for Tarot Today

When I look at the cards in a tarot deck now, I find myself thinking about those Egyptian craftsmen painting intricate patterns onto paperboard in a Cairo workshop six or seven centuries ago. They had no idea they were creating something that would travel across the Mediterranean, mutate and evolve, and eventually become part of a global phenomenon.

This history matters because it complicates the narratives we often hear about tarot. Some people claim tarot has ancient Egyptian origins, which isn’t quite accurate but isn’t entirely wrong either. The Mamluk connection is real, but it’s also indirect. The cards traveled and changed. They were adapted to new contexts, new cultures, new purposes.

Understanding this lineage also offers a different perspective on the Minor Arcana. These aren’t just the “boring” cards compared to the visually dramatic Major Arcana. They’re the carriers of a structural DNA that has survived remarkably intact for centuries. The four suits, the progression from ace to ten, the hierarchy of court cards, all of this comes from that original Mamluk system.

Perhaps there’s something to reflect on in the symbolism itself. Cups, swords, coins, and batons (or wands) represent aspects of human experience that transcended their original cultural context. They spoke to something universal enough that they could be adopted across religious and linguistic boundaries. They worked in Islamic Cairo and Christian Venice alike.

The Gaps in Our Knowledge

I should acknowledge that much about Mamluk cards remains uncertain. Very few original Mamluk decks have survived to the present day. The fragments and complete cards that exist are scattered across various museums and private collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has some pieces. The Topkapi Palace in Istanbul houses others. But we’re working from incomplete evidence.

We don’t know exactly when the first Mamluk cards were created, or who designed them, or even precisely how they were used. Were they primarily gambling tools? Were there specific games associated with them? How widespread were they within Mamluk society, or were they confined to elite circles?

These gaps frustrate historians, but they also leave room for continued discovery. New evidence could emerge. Better analysis of existing artifacts might reveal details we’ve missed. The story isn’t finished being written.

A Legacy That Endures

The next time you shuffle a tarot deck or lay out a spread, consider the journey those cards represent. From Cairo to Venice, from polo sticks to wands, from geometric patterns to illustrated figures, the evolution spans centuries and cultures. The Mamluk cards weren’t tarot, not yet, but they contained the seed of what tarot would become.

That connection feels important to me. It suggests that tarot, whatever else it might be, is fundamentally a product of cultural exchange and adaptation. It emerged from contact between different worlds, different ways of seeing and organizing experience. The cards carry that history within their structure, even when we’re focused on their symbolic or reflective possibilities.

Learning about Mamluk cards doesn’t change how I use tarot for personal reflection or creative exploration. But it does add depth. It reminds me that these cards have roots extending further back than I initially imagined, and that their journey into the present has been anything but straightforward. Sometimes the history itself becomes a kind of mirror, reflecting back unexpected connections across time and space.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where can you see original Mamluk cards today?

The most complete surviving Mamluk deck is housed in the Topkapi Museum in Istanbul, consisting of 47 cards from what was originally a 52-card deck. Some fragments also exist in other collections, though very few original Mamluk decks have survived to the present day. Modern reconstructions of these cards are available for collectors and historians interested in experiencing this historical deck firsthand.

Why didn’t Mamluk cards show human figures like European cards do?

Mamluk court cards featured only calligraphic text with the rank titles rather than pictorial representations of people, which has been attributed to Islamic artistic traditions that often avoided depicting human figures. However, it’s worth noting that this may have also been a stylistic choice rather than strictly religious, as other Mamluk manuscripts from the period do contain human imagery. When Italian card makers adopted the structure, they replaced these text-based designs with illustrated kings, knights, and pages.

Did Mamluk cards have only three court cards per suit or four?

There’s ongoing debate among historians about whether Mamluk decks had three or four court cards per suit, largely due to the incomplete nature of surviving decks and the presence of replacement cards. The three ranks clearly identified are the king, deputy, and second deputy, with some scholars suggesting an earlier version may have had only two court cards similar to Persian Ganjifa cards. This controversy highlights how much we’re still learning about these fascinating cards.

Can you use Mamluk cards for tarot readings or divination?

While Mamluk cards represent a complete Minor Arcana structure with 56 cards, they lack the symbolic imagery typically used in tarot reading and have no Major Arcana. Some practitioners use reconstructed Mamluk decks for meditation, scrying, or developing intuition by gazing into the intricate geometric patterns, which can spark imagination in ways different from traditional illustrated tarot. They’re better suited as historical artifacts or contemplative tools rather than conventional divination decks.